The project needed to be sensitive to the needs of our young participants. Whilst new arrivals can outwardly exhibit strong resilience, privately they are often dealing with trauma and grief, whilst some still need to be vigilant because of continued risk of trafficking. We understood the need to be aware that our participants might have, and continue to, experience trauma but we did not want this to be the focus of our interactions with them. We sought advice from those with expertise and the research instruments were designed collaboratively with representatives from those working with refugee communities. Whilst we were mindful to position our participants as ‘knowledge- holders’ (Lenette, 2019) we acknowledge that our ambition to give voice to those with lived experience of forced migration is wholly dependent upon a reciprocal commitment from the research team, practitioners, municipal planners and policymakers to be able to listen ‘with intent’ (ibid., p. 17) if these voices are to be heard.

Firstly, we conducted interviews with key stakeholders within each city and conducted a desk-based review of recent arts and cultural activity for young people including that aimed at new arrivals. Through this we began to understand how the municipality currently work to develop cultural citizenship for young people, the perceptions of young migrants of their new place, and the response of the host communities to young new arrivals. We then worked with artists who had worked with refugee groups before to develop a planned programme of arts and cultural activity and visits to cultural places within the cities of Nottingham and Lund.

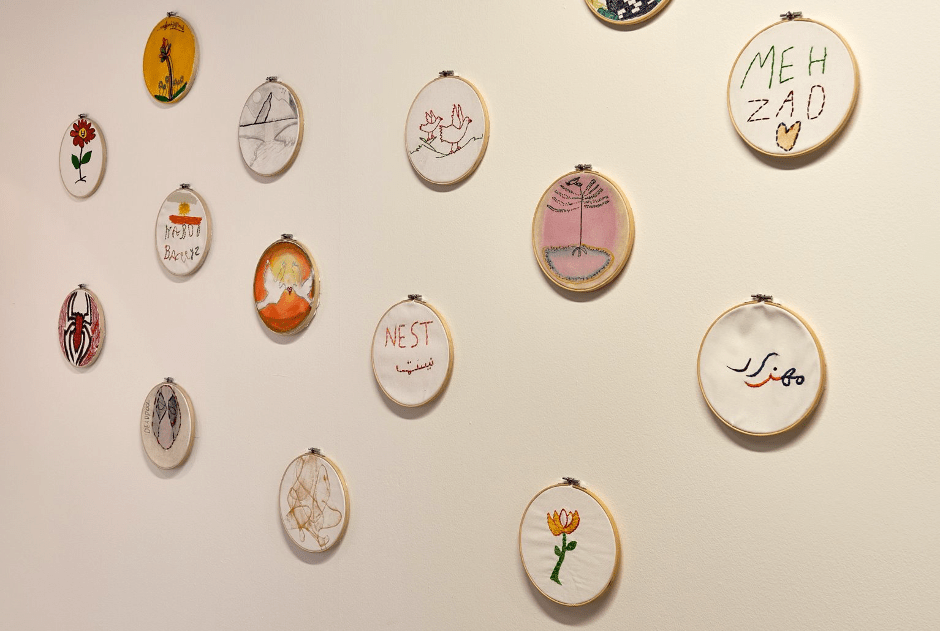

We conducted an ethnographically-informed study comprising close observation of each session within this programme, documenting what the participants did through photographs and fieldnotes. We used the method of photo-elicitation drawing on these images in our interviews with the young participants. In Nottingham this comprised 14 interviews and in Lund 11 young people were interviewed. We drew on photographs and our fieldnotes as aids to the conversation. The interviews were conducted in English or Swedish with the aid of the young people’s translation apps on their mobile phones when necessary. In Nottingham, the project culminated in a public art exhibition featuring the work of 39 young new arrivals in an iconic local art gallery, the New Art Exchange. Many of the young people were unaccompanied and all aged between 15-18; the group was largely made up of males though a small group of girls joined in the last weeks. The participants’ distinctive cultural contributions to the workshops and final public exhibition reflected countries from across the world, including Afghanistan, Eritrea, Iraq, Iran, Vietnam, Syria, and Sudan. Kurdish voices were also strongly represented.

In Lund there were 22 participants between 11 and 21 years of age attending daily during the workshop period. Of these 21 were female and one was male. They were living in Lund, the nearby city of Malmö, or in close by areas such as Eslöv and Kävlinge. Since some of the participants articulated about their national background being of less interest and that they felt this was positive, there was no gathering of this data within the Swedish part of the project. During the summer holiday a school in the centre of Lund worked as a daily gathering point for art work. The project culminated in a public exhibition at Kulturen, both an indoor and an open-air museum that features historic buildings but also different exhibitions ranging from folk art to modern design, from local to global culture.

The conceptual thinking underpinning this study foregrounds the dialogic relationship between the individual migrant youth and the spaces they interact with in their new communities. It has been influenced by Kraftl’s provocation to focus on developing inclusive spaces for young people in cities through practices that enhance recognition, participation, support and collaboration in order to develop the social and cultural value of these spaces for those who are marginalised (Kraftl, 2020). Two theoretical framings are central: art as place-making activity, and cultural capabilities. First, people engage in place-making through arts and cultural activity and this brings about increased ‘points of connection’ (Lankshear & Knobel, 2011) to communities and places. Second, a capabilities approach enables us to focus on ‘What … people really (are) able to do and what kind of person are they able to be’ in a place (Robeyns, 2017, p. 9). We want to shift the focus from outcomes that are viewed instrumentally in relation to the labour market, to a process of recognition (Honneth, 1992) that enhances individuals’ capability and capacity to aspire on an individual as well as collective level, leading to enhanced experiences of cultural citizenship for new arrivals and their new communities.

The programme built on Nottingham’s existing use of the Cultural Rucksack approach.

Cultural Rucksack

The Cultural Rucksack originated in Norway in 2003 and is a national programme for culture and arts for schools. It has national government funding as it is ‘at the core of the Government’s policy of making culture and the arts available to all children and youth. It is intended to allow school pupils to become familiar with, understand and appreciate different forms of artistic expression at the professional level’ (UNESCO, 2012). The Cultural Education Partnership, ChalleNGe, in Nottingham has adapted the concept of the Cultural Rucksack. Nottingham’s Cultural Rucksack brings together schools with artists, creative practitioners and cultural institutions and organisations in the city: ‘We believe every child and young person is entitled to a broad range of arts and cultural experiences that can lead to life-long engagement with creativity and the arts.’ (ChalleNGenottingham, 2022). Schools and arts providers each sign up to a commitment pledging their offer and potential contribution to the development of the Cultural Rucksack offer. In this way schools and creatives are working together to plan a programme of arts and cultural activity across a child’s school experience. The ChalleNGe board have mapped where cultural organisations and opportunities are for schools to access across the city and have also developed curriculum ladders for schools highlighting strong creative practice. There are regular Culture Meets bringing together schools and the arts providers. In this way the Cultural Rucksack is:

drawing together inspirational arts experiences, devised jointly by teachers and creative organisations to align with the school curriculum and met the needs, aspirations and interests of young people. Celebrating the rich heritage and cultural diversity of Nottingham is also an important element fo the Cultural Rucksack, ensuring young people grow up feeling connected to and valued by their city (ibid.).

Evaluations of the Cultural Rucksack programme are overwhelmingly positive, but there are a number of challenges and criticisms, most notably the critique of its role as a means of ‘civilizing’ the population (Bjørnsen, 2012), with inherent notions of what counts as art and what participation looks like (Christophersen, et al., 2015).

The first stage of the project sought to establish the enabling factors and barriers to social and cultural participation for newly arrived forced/involuntary migrants in each case study context. In the following case studies, we firstly introduce each city’s context by drawing draw on the analysis of web-based publicly available documentation and interviews with key stakeholders within Nottingham and Lund. We then report details of the iteration of the Art of Belonging Cultural Rucksack programme in each context.